Yes, it is actually possible to grow whilst cutting costs…

Despair not and come out of the Corona virus crisis as a winner

by Niklas Hageback

A compiled excerpt from a forthcoming book on digital leadership due for publication in late 2020

NIKLAS HAGEBACK. The outbreak of the Corona virus is causing dire economic effects with companies across industries being badly affected from a dramatic slump in demand, and some already starring into the abyss with imminent bankruptcies looming. Where growth was everyone’s strategy only a few weeks ago, quite literally staying alive is now the only thing that matters. But in the midst of all this human and financial hardships, opportunity lurks, this as a resourceful leadership can turn this crisis it into a watershed moment, utilising to its advantage the momentum for change that has been provided and quickly reset the organisation to higher productivity and growth whilst the competition are at peril of succumbing. This might be an equation you thought not solvable, and no, proposed is not a ‘fortune favours the bold’ approach, but au contraire the reduction of risks and costs work as enablers for productivity and growth.

There are costs and then there are costs…

This acute focus on costs is now an almost forgotten skill, as over the last decade with the global economy recovering quickly after the financial crisis of 2008, spurred by an unprecedented loose monetary policy, cost only played a minor role as executives crafted growth strategies, in particular by deploying the latest in digital technologies. Spending more with a view to grow more has been a mantra to live by, and it by and large made sense in a low interest environment, but as a side effect slack has been allowed to fester. However, now an urgent shock therapy is required forcing punch drunk business leaders to oversee heavy handed amputations simply to stop the bleeding, a dicey undertaking, always at risk of killing the patients they are trying to save.

To start with, costs need to be assessed, segmented and prioritised, in its most broad brushed form, one can delineate between cost cutting and cost optimisation, terms that tend to be interchangeably used but are actually distinct. A cost assessment seeks to create a more viable cost baseline, detailed at geographical and business unit levels, by ascertaining and then executing the necessary cost cuts and cost optimisations to reach a new baseline.

Now, the Corona virus has forced many businesses to swiftly migrate to exclusively use virtual meetings and working-from-home facilities, and interestingly enough but rarely realised and capitalised on, these arrangements are nothing but a gigantic cost assessment, where in effect the minimum inputs are determined, i.e. which processes can we altogether skip?, which meetings can we eliminate?, and which people do we not really need to participate in these meetings and processes to keep the business going? As a case in point, the very nature of virtual meetings make them much more succinct than in-real-life meetings, and the group dynamics will drastically change, the previously dominating windbags hijacking meetings with a constant oratory of platitudes and smooth talking will fade out, as ambiguities and nonsense really does not fare well in a virtual setting, and instead the straight talker with meaningful and productive content, usually backed up by action, will come to dominate. For the observant and perceptive leader, this can serve as a true wake-up call to realise who the value-adding contributors of the firm are, and the ones that rarely delivers, and use these insights to calibrate the team compositions to achieve cost efficiency and productivity improvements. So, by acknowledging the productivity perspective through these temporary re-designs of processes and the meeting bureaucracy, they become an important part of a cost assessment workout, obviously needing to adjust for more permanent arrangements that introduce a new way of working, forming the backbone of a leaner organisation. A comprehensive cost assessment exercise takes aim at a number of factors;

· Reduce bureaucracy by removing organisational layers;

· Clarify roles and responsibilities and terminate duplicates;

· Eliminate redundant or irrelevant functions, processes, or activities;

· Consolidate functions where possible;

· Applying lean techniques to repeatable or low-value processes;

· Reconsider the role of the corporate center, and;

· Seek to introduce digital solutions to automate activities.

In essence, cost cutting refers to imminent actions aimed at slashing expenses not considered critical for business, such as elimination of certain staff, typically contractors and consultants, consolidation of duplicate functions, the ban of business travels, but also pay cuts and other benefits reductions. Any costs that can be reduced immediately with no or little negative effect on revenues but with direct cost reducing impacts must be considered. A cost cutting workout should follow a one-off assault approach, expedited through a crisis management ethos that instills a sense of urgency, which provides a window of opportunity to push through and gain support for the necessary drastic measures. The momentum is kept going through daily gatherings to keep close track, monitor progress and broadcast status of the assigned performance metrics, typically dollar amounts and dates, until the targets are reached.

Cost optimisation, on the other hand, is rather than a one-off immediate undertaking, a continuous effort specifically designed to drive spending- and cost reductions while maximising business value, by applying a strategy perspective on where the business should be, and in where a digital transformation will play a pivotal role. A cost optimisation au contraire to cost cutting will include investments while still engaging in reducing costs, ideally aspiring to balance these out, but mismatches in cashflow are likely to occur and ensuring that credit lines are kept open must be part of this strategy. To in times of economic downturns, invest in various digital tools might be regarded as a hazardous proposition, but it has proved to be the epitome of what is considered a sound investment and has stood the test of time, as both technology, as well as, high value-add employees can be obtain for a discount. Thus, cost optimisation consider factors such as;

· The core business model and its product and service focus; whether to enter or exit businesses, geographies, joint ventures, and in particular looking at low growth- and/or low margin activities;

· A rethink of the organisational design, including the relationships between the corporate centre and the business units;

· Resolve any unfinished projects, such as incomplete merger integrations or abort/delay potential takeover plans, and;

· Identify weak spots in the organisation, which could be due to a raft of factors, including, unnecessary complexity slowing down processes, not employing productive enough people, poor leadership, extensive bureaucracy, and systems and applications needing upgrades or complete revamps.

In many of the above areas, digital tools will help to streamline processes, reduce labour costs through automation, and by disrupting existing business models one can develop new capacities based on digital capabilities which open the door to new commercial opportunities, making it possible to distinguish oneself in the marketplace and increase revenues. Some key strategic areas, but far from all, where digital transformations should cover are;

· Process automation, by mapping out the steps of the process apt for automation, for manufacturing finding solutions in robotics and leverage Internet of Things to build intelligent business processes. For service providers, seek out suitable AI applications, such as virtual assistants and various types of bots.

· Optimise supply chains through increased automation

· Reduce inventory by deploying automation, therby minimise stockpiling and improve the balance sheet

· Outsource less vital functions to low cost providers

· Advance the integration of CRM systems to become an essential part of the sales function

· Digitise the customer journey and provide customer self-service technologies, which must be continuously updated and established on the customer perspectives and experiences.

· Employ data analytics in a pro-active manner to identify new commercial opportunities, improve customer retention and marketing responses.

· Improving data management, facilitate access to data across the organisation, seek where possible to offer real-time information and encourage employees to share and use data allowing for faster, and hopefully better, decisions and the creation of business value.

With costs coming under control, engage Growth Hack

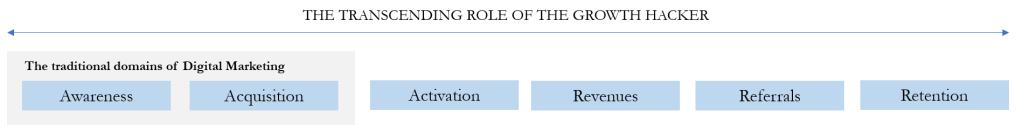

The last couple of bullet points alluded to areas where digital transformations in addition to reducing costs also provide entrepreneurial approaches to grow the business, in both new and existing areas. As the collation of customer data and a tracking of their behaviour can be fashioned in a more structured way through repositories, allowing for business intelligence- and data analytics tools to identify commercial patterns of a dynamic nature, notably giving an opportunity to understand market trends for an economy in recession and to develop service and product offerings for such meager conditions.

The growth hackers need to work in close conjunction with the marketing team, with somewhat blurred boundaries on where responsibilities start and end respectively.

As the depiction highlights, cost cutting, cost optimisation and growth hack can through a consolidated manner by being executed in concert, reduce costs and risks, and at the same time spur productivity and growth.

Who is best set to lead this effort?

A venture of this scale is nothing but a radical transformation of the organisation, leaving no stones unturned, affecting everything and everyone. By necessity, invasive and all-encompassing, with many moving pieces that needs delicate co-ordination, and it goes without saying that timing and speed will be mission critical, that can be enabled through Agile methods ‘on steroids’, this as delays risk de-railing an otherwise well thought-through execution plan.

Thus, to oversee and manage this highly complex type of enterprise will require nothing less than a leadership extraordinaire, and the plain Jane/James type change manager need not even apply, as the role demands considerable talents, an exceptional capacity for lateral thinking, backed by a multitude of experiences extending far beyond only a technical competency, highlighted through a helicopter perspective truly understanding all aspects of the business architecture. And last but probably most important, the person in charge needs a personality that radiates the rare high energy ‘can do’ leadership quality to be able to swiftly and as required, relentlessly deal with the problems that are bound to arise along the way.

These qualities are occasionally, but far from always, bestowed only a handful of senior executives within the organisation, such as the CEO, the COO and Head of Sales. But they will generally be too busy with their daily activities and routines, and in times of crisis constantly called for to broadcast reassuring messages through various communiques and townhall meetings to both internal and external stakeholders, not least worried creditors and investors. By being engaged in other activities, it will severely slow down the accelerated pace required to plan and execute, a crucial success factor which can only be achieved through a dedicated leadership commitment. Then there are sentimental aspects to consider, as it requires staying emotionally detached to not allow for nostalgic sentiments to certain functions, products or staff, to cloud one’s judgement in making the correct but painful decisions, something long serving members of an organisation might not always be capable of, emotionally burdened by various vested interests. Hence, all considered, engaging an independent consulting firm with extensive pedigree in comprehensive and commercially sound transformations is probably the way to go.

Way Forward

Make sure to pre-order your copy of Leadership in the Digital Era – Renaissance of the Renaissance Man for a detailed outline on how an integrated cost cutting- and digital transformation strategy will deliver rapid productivity improvements and growth in a time when your less informed competition is fighting for survival!